Nicotine, the primary active compound in tobacco, is predominantly known for its stimulating effects on the central nervous system (CNS) and its widespread use as a drug, ranking second only to caffeine in popularity. Despite its limited therapeutic applications, nicotine remains a significant public health concern due to its addictive nature and association with severe health risks, particularly when consumed through smoking.

Historical Background of Nicotine

Nicotine, derived from tobacco plants, has a rich historical background dating back centuries:

Early Use and Discovery

- Native American Origins: Tobacco use, including the consumption of nicotine, traces back to indigenous cultures in the Americas, where tobacco was cultivated and used ceremonially and medicinally.

- European Discovery: Nicotine was first isolated in 1828 by Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and Karl Ludwig Reimann from tobacco leaves. Its name originates from Jean Nicot de Villemain, the French ambassador to Portugal who introduced tobacco to the French court in the 16th century.

Industrialization and Popularization

- Cigarette Revolution: The invention of the cigarette rolling machine in the late 19th century led to the mass production and widespread consumption of tobacco products, dramatically increasing nicotine exposure worldwide.

- Marketing and Cultural Influence: Throughout the 20th century, tobacco companies heavily marketed cigarettes, promoting them as symbols of sophistication, relaxation, and social status. This era saw a surge in nicotine consumption despite growing awareness of its health risks.

Scientific Discoveries and Health Concerns

- Health Risks: By the mid-20th century, scientific studies conclusively linked nicotine to a range of health issues, including lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and addiction. This prompted public health campaigns and legislative efforts to curb tobacco use.

- Regulation and Awareness: Governments worldwide began implementing strict regulations on tobacco advertising, sales to minors, and public smoking. Awareness campaigns highlighted nicotine’s addictive properties and its role in the global burden of disease.

Contemporary Issues and Regulation

- Tobacco Control Efforts: In recent decades, efforts to reduce nicotine consumption have intensified with smoking bans, taxation policies, and smoking cessation programs. The rise of alternative nicotine delivery systems such as e-cigarettes has introduced new challenges and debates regarding their safety and efficacy.

- Global Impact: Nicotine addiction remains a significant global health challenge, with efforts focused on reducing smoking prevalence, especially among vulnerable populations. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) represents a landmark international treaty aimed at reducing tobacco use and its associated health impacts.

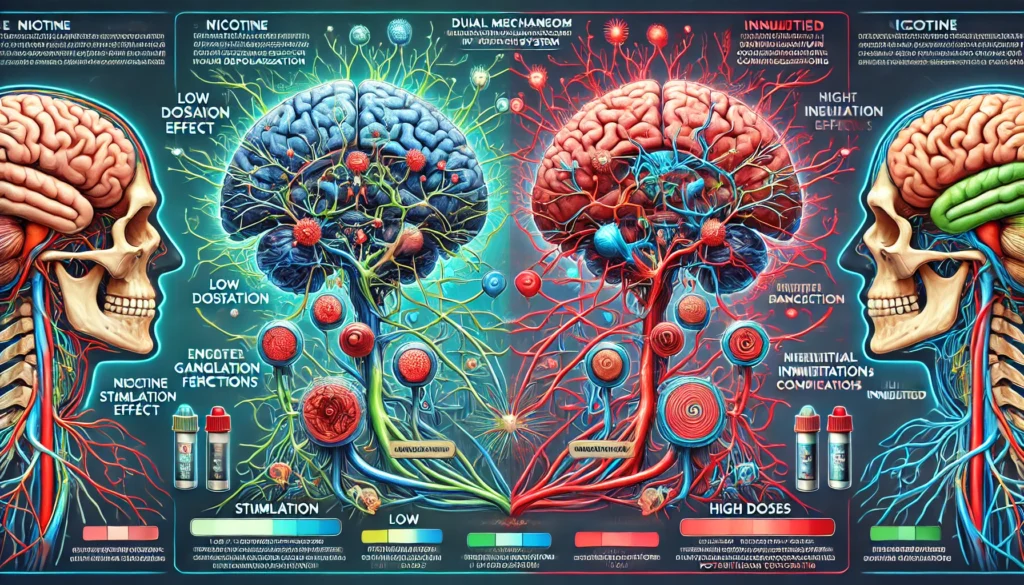

Mechanism of Action

Nicotine operates through a dual mechanism depending on dosage levels. At low doses, it stimulates ganglia via depolarization, whereas at higher doses, it blocks ganglionic function. The presence of nicotine receptors throughout the CNS contributes to its stimulant properties, affecting various cognitive functions such as attention, learning, problem-solving, and reaction times. This dual action underscores both its appeal and its potential for harm, particularly in higher quantities leading to respiratory and cardiovascular complications.

Pharmacokinetics

Nicotine’s high lipid solubility facilitates rapid absorption through multiple routes, including oral mucosa, lungs, gastrointestinal tract mucosa, and skin. This enables efficient passage across the blood-brain barrier, enhancing its psychoactive effects. Smokers typically absorb 1 to 2 mg of nicotine per cigarette, with a lethal dose estimated at 60 mg. Metabolism occurs primarily in the lungs and liver, followed by urinary excretion. Notably, tolerance to nicotine develops quickly, necessitating higher doses over time to achieve the same effect.

Effects on the Central Nervous System

Nicotine induces a range of CNS effects, from mild euphoria and relaxation at lower doses to severe symptoms such as irritability and tremors at higher doses. These effects underscore its potential for addiction and dependency, as well as its role in altering the metabolism of other drugs, complicating treatment strategies for co-occurring conditions.

Peripheral Effects

Peripherally, nicotine stimulates sympathetic ganglia and the adrenal medulla, resulting in increased blood pressure and heart rate. This poses significant risks for individuals with hypertension and cardiovascular disease, exacerbating symptoms and potentially compromising overall health. Furthermore, nicotine-induced vasoconstriction reduces coronary blood flow, posing risks for patients with angina and other cardiovascular conditions.

Adverse Effects and Withdrawal Syndrome

The addictive nature of nicotine leads to rapid development of physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms upon cessation. Withdrawal symptoms include irritability, anxiety, restlessness, difficulty concentrating, headaches, insomnia, changes in appetite, and gastrointestinal disturbances. Nicotine replacement therapies such as transdermal patches and nicotine gum have proven effective in managing withdrawal symptoms and supporting smoking cessation efforts by providing controlled doses of nicotine.

Conclusion

In conclusion, nicotine’s status as a widely used CNS stimulant underscores its dual nature as both a popular substance for its stimulating effects and a significant health risk due to its addictive properties and association with serious illnesses. Understanding its mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, and adverse effects is crucial for developing effective cessation strategies and mitigating its impact on public health.