Guanethidine

Guanethidine and related adrenergic neuron-blocking agents are drugs primarily used to lower blood pressure by disrupting the release of norepinephrine from postganglionic sympathetic neurons. Guanethidine, once a cornerstone in treating severe hypertension, induces profound sympathoplegia, significantly reducing sympathetic nervous system activity. However, due to its severe side effects such as marked postural hypotension, diarrhea, and impaired ejaculation, its use has dwindled. Notably, guanethidine’s inability to cross the blood-brain barrier prevents central nervous system effects seen with other antihypertensive medications.

Mechanism of action

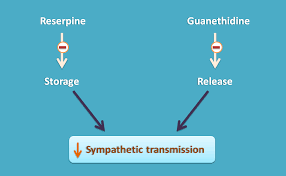

Mechanistically, guanethidine inhibits norepinephrine release by entering sympathetic nerve endings through the same transport system used by norepinephrine itself. Once inside, it displaces norepinephrine from vesicles, leading to gradual depletion of norepinephrine stores. This depletion underlies its antihypertensive action, making neuronal uptake essential for its effectiveness. Drugs that interfere with this uptake process, like cocaine or certain antidepressants, can diminish guanethidine’s efficacy.

Pharmacokinetics

In terms of pharmacokinetics, guanethidine has a notably long half-life of approximately 5 days, resulting in a gradual onset of action (1-2 weeks to reach maximal effect) and persistence of effects even after therapy cessation. Dosage adjustments must be spaced apart to avoid sudden increases in hypotensive effects. However, its therapeutic use commonly associates with symptomatic hypotension, especially postural hypotension, and exercise-induced hypotension, particularly at higher doses. Men may also experience delayed ejaculation due to its sympathoplegic effects.

Toxicology

Adverse interactions further complicate guanethidine therapy. Concomitant use of sympathomimetic agents or tricyclic antidepressants can counteract its antihypertensive effects or even lead to hypertensive crises. Thus, careful management and monitoring are essential when prescribing guanethidine, particularly in patients with complex medical histories.

Reserpine

Reserpine, derived from Rauwolfia serpentina, shares some mechanistic similarities with guanethidine in its action against hypertension. Reserpine blocks the uptake and storage of biogenic amines in vesicles, depleting stores of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin throughout the body. This action, however, occurs not only in sympathetic neurons but also in adrenal chromaffin cells, albeit to a lesser extent.

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacological effects of reserpine on blood pressure include a reduction in both cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance, achieved through long-term use at lower doses. Unlike guanethidine, reserpine readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, affecting central nervous system amine stores and potentially causing sedation, depression, or symptoms resembling Parkinson’s disease.

Toxicology

Despite its efficacy in lowering blood pressure, reserpine’s use has declined due to significant side effects. High doses may induce sedation, mental depression, and gastrointestinal disturbances like increased gastric acid secretion and mild diarrhea. Even low doses can occasionally lead to extrapyramidal effects resembling Parkinsonism, making it unsuitable for patients with a history of mental health issues.

In summary, while both guanethidine and reserpine have historically played roles in managing hypertension, their use today is limited by severe side effects and interactions. Guanethidine’s sympathoplegic effects and pharmacokinetic profile necessitate careful dosing and monitoring, particularly in high-risk patients. Reserpine, on the other hand, poses risks of central nervous system disturbances and gastrointestinal issues, warranting caution in its prescription. Advances in pharmacology have led to safer alternatives, reducing the prominence of these once-mainstay treatments in contemporary hypertension management.

Conclusion

In conclusion, guanethidine and reserpine, once pivotal in the treatment of hypertension, have gradually fallen out of favor due to their significant side effect profiles and interactions with other medications. Guanethidine acts by inhibiting the release of norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons, resulting in sympathoplegia and lowering blood pressure. Its inability to cross the blood-brain barrier limits central nervous system effects but contributes to adverse effects such as severe postural hypotension, gastrointestinal disturbances, and sexual dysfunction.

On the other hand, reserpine depletes biogenic amines from vesicles throughout the body, including in sympathetic neurons and adrenal chromaffin cells, thereby reducing blood pressure by decreasing cardiac output and peripheral vascular resistance. However, its ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier can lead to central side effects like sedation, depression, and potential extrapyramidal symptoms.

Both drugs require cautious dosing and monitoring due to their long half-lives and the risk of severe adverse reactions. Guanethidine’s interactions with sympathomimetic agents and antidepressants can provoke hypertensive crises, while reserpine’s propensity for causing sedation, mental depression, and gastrointestinal disturbances limits its use, especially in patients with a history of mental health disorders.

In contemporary hypertension management, the decline in the use of guanethidine and reserpine reflects advancements in pharmacology that have introduced safer alternatives with more predictable efficacy and fewer side effects. These newer agents target hypertension through different mechanisms while minimizing adverse reactions, thereby offering improved outcomes and tolerability for patients with high blood pressure. As such, while guanethidine and reserpine contributed significantly to the understanding and treatment of hypertension, their historical prominence has given way to more refined therapeutic approaches in modern medicine.